This post will be one a several that will share my experiences on a recent trip to the Northwest Territories. In this post, I answer readers who asked questions such as: “I want to know the low-lights, in addition to the highlights”; “Could I do this trip?”; “How hard was it?” Contrary to many trip reports that I read, there is no such thing as a trip that is all rainbows and unicorns. Usually, I don’t get too personal in my blog posts. I’m going to risk it here so that I can respond to these kinds of questions.

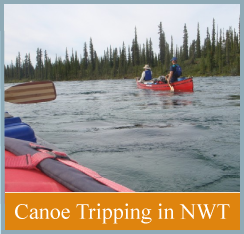

I knew that a 6-day canoe trek would be both a physical and mental challenge for me. Physical, because my body is not used to paddling for hours each day. And mental, because I’d need to push myself through the physical challenges and keep myself positive.

The first day of our trek was the most difficult for me.

While our two Canoe North Adventures guides, Cedar and Courtney, packed up the float plane with our gear, I was trying to ward off my anxiety about leaving cell phone access. While out on a trip, the lead guide uses a satellite phone to check-in each evening, so we could be reached if my kids needed me. But even knowing that we would not be completely inaccessible did not help much. It just goes to show how reliant we have become on instantaneous access within the relative short time that cell phones have become standard personal gadgets.

North-Wright Air is located right beside the Canoe North Lodge in Norman Wells, NWT.

Leaving the land of easy accessibility was only one element contributing to my trepidation that morning. In recent years, I’ve developed a dislike for small spaces. Well, not necessarily small per se but rather spaces that I can’t easily walk out of — like a tunnel, cave, or a even a large crowded auditorium that has only one exit but on the very far side from where I am. As you can imagine, sitting in a plane after the doors have been closed is included in this list.

I first learned the extent of my new dislike for these kinds of spaces when I suffered a full-blown panic attack on a runway and had to be de-boarded from a plane. It was both a humiliating and hugely disappointing experience (I was leaving for a trip to visit my sister in South Korea). If you’ve never had a panic attack, which I hadn’t until that point, I can tell you it feels like you are going to die. Honestly, it really does. Naturally, I’ve since consulted with my doctor and learned that although it feels like you can’t get enough air into your body and that your heart is going into some kind of seizure, you can’t actually die from a panic attack. This information has helped me a great deal. That, and carrying a small supply of quick-acting anti-anxiety medication for emergency use.

Room was tight in the float plane. Three adults in the back. Two in the front.

I simply cannot stop flying. We have family overseas. We want to show our kids the world. It’s just not an option for me to let this fear take over. Since that first panic attack, I’ve taken several plane rides. I’ve been to Halifax, Seattle, Chicago, and even Jamaica. Some are easier than others. Usually, if I can distract myself away from looking at the plane’s walls or doors by reading, I can suspend belief. This was my plan for the float plane: suspend belief by keeping my face towards the window and distracting myself with the gorgeous scenery.

Aerial view of Great Bear River from the float plane. (Photo credit: Courtney Terriah)

It worked for about 15 minutes of the 40-minute flight. Then the tingling feeling began in my fingers, and my chest began to tighten. I kept my face towards the window and pushed my backpack into my husband’s lap. He knew what that meant. He found my medication and gave me one of the itty bitty pills while I kept focusing on my breathing. The rest of the trip was about as pleasant as the experience of labour contractions.

When we finally landed on the water and I could get out, my legs were so wobbly. But I had survived it. I scrambled up onto the shore and sat down in the tundra to catch my breath and try to regain some composure. The pilot and our two guides were all quite young, and I could only imagine what they thought of me, this chubby middle-aged lady with a tear-stained face.

So happy to be on solid ground, touching the tundra.

If they doubted my ability to do the trek, they didn’t show it. Cedar sat with me for a bit. He spoke kindly but without condescension and let me know that I could take as much time as I needed. I told him that I wasn’t sure I could do that plane ride on the way back. He explained that we were canoeing all the way back to the lodge; no more planes. Relief washed over me.

After about 10 minutes, I got up and went back to the shore. “Okay, I’m ready.”

Ready to canoe from one shore of Great Bear Lake to the other to set up camp.

At this point, it was already about 5 or 6 pm. But time is hard to tell out in the North at this time of year. The sun is out all day, and all night. We didn’t have far to go. We were simply going to canoe across to the opposite shore, where we’d set up camp and then have some dinner.

Awaiting us on the opposite shore were a ridiculous amount of mosquitoes. I knew that it wasn’t just me being “soft,” because I could see that even the guides were a bit surprised by how many of them were feasting upon our flesh.

Cedar, one of our Canoe North Adventures guides, sits under our dinner tarp with many uninvited guests. (Photo credit: Courtney Terriah)

Unlike the guides, who I never saw apply bug spray or sunscreen throughout the entire trip, I immediately set about dousing myself in strong chemicals. I also put on a bug hat that I’d brought. It was extremely fashionable, as you can see. In fact, all supermodels might want to take to wearing one since it acts as an effective weight-loss tool because you don’t want to risk lifting away the net to eat!

Bug hats are the new black.

As soon as dinner was finished, I excused myself to the privacy of our tent. I may have cried a little.

Laying in the tent after a challenging day. What had I gotten myself into?

I was exhausted from a long day that had started off in Yellowknife. I was exhausted from the panic on the float plane. I was exhausted from trying to put on my “happy face.” But thankfully I was too exhausted to worry about how I would survive 5 more days of this. Instead, I fell into a sleep so deep that not even a bear in the tent could have woken me.

And with that, I closed-out one of the most challenging days of my life. Meanwhile, my traveling companion had experienced one the best days of his life.

Fly fishing in the mouth of Great Bear River. Note how clear the water is. (Photo credit: Julie Harrison)

P.S. Want to know why I shared these tough moments? I answer that question here.

Speak Your Mind